Confession: I don’t watch movies. In fact, I hate movies. Whenever anyone asks me if I want to watch a movie, my immediate response is to punch that person in the face. Maybe you think I’m exaggerating. The beau has had his nose broken five times.

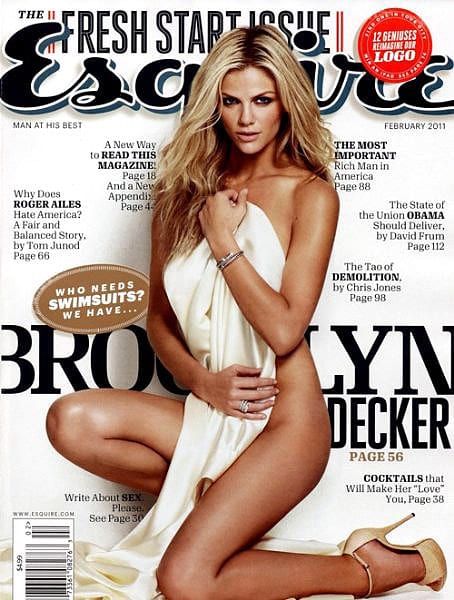

All this is to say I don’t know much about movies, or the celebrities who are cast in them. Or celebrities in general, really. Which naturally leads us, as it does, to the one celebrity I seem to be marginally conscious of: Brooklyn Decker. It’s appalling to think that there was once a time in the not-so-distant past when I did not know a person named Brooklyn Decker even existed! Fortunately, the intense kinship I felt with her during the brief half hour I thought her name was Lyn Decker has forever seared her name indelibly into my squishy grey matter. This has helped, too:

I know what you’re thinking: that cover? Again? Seriously? This is the third time you’ve slapped that thing up on your blog. If I didn’t know any better, I’d think you were fishing for new male readers. What gives, man?

What gives? I finally read that article, man. In Esquire. The one about Brooklyn Decker.

And guys, it’s bad.

Here’s the premise. Our author-hero, Tom Chiarella, goes over to Brooklyn’s apartment in Brooklyn (meta!), New York, where they talk and she cooks him a chicken dinner. Mr. Chiarella — do you think I can just call him Tom? Do you think he’d mind? — then attempts to summarize her physicality and personality in just under 3,100 words. He attempts to get a handle on Who Brooklyn Is. To allow the reader to step into his shoes and experience Brooklyn for himself. Tom is selfless like that — only the Lord’s work will do for Tom.

Along the way Tom makes a variety of statements that I found… interesting. I found them so interesting that I actually dug out a highlighter and spent the better part of an hour bathing large swaths of text in yellow. For the sake of brevity, I’ve limited the quotes to the following selections. Should you desire to read the entire article, here’s the full text.

Onward.

Light of heart and unexpectant, she gives the impression that being present is easy, that passing time talking with a man she doesn’t know is exactly what she wants to do on a Friday night in New York. She makes her little salad. What do I like? What do I not like? She even seems a little curious about my preferences. I’m cool with whatever, I say. I can handle anything she dishes up. But Brooklyn doesn’t cook like that. She doesn’t want to disappoint. She just wants me to like it. There is no protest or resistance in her voice. It’s just something she can do.

Oh, hello stranger! I am only too happy to acquiesce to your needs. Please tell me what your needs are! I am here for them. No, no. Really! I wouldn’t want to disappoint.

At twenty-two she married Andy Roddick, the only appealing American tennis player with gonads. Young, right? She was then merely a swimsuit model and may in fact be only that now: known for her frame, for her confident carriage in body paint, for the slope of the back of her legs, for eyes that issue the command Get over here. And the breasts, ah, yes, always the breasts. It’d be foolish, and a little dishonest, to mention her history of swimsuit modeling, to allude to the Sports Illustrated cover and to the myriad catalogs of her image on the Internet without mentioning her breasts. They are not much evident tonight, here in the kitchen. She plays smaller in her own space, in a sweater and jeans like a lonely college girl, the kind who keeps her body a secret. But there they are. Have a look. She does not mind — she can’t. Fill in your own simile. Just don’t make her less than her whole in so doing.

Less… than her whole of what? According to Tom, her whole appears to be limited to a smattering of body parts. It’s okay though, she’s merely a swimsuit model. She cannot mind if she does not have one.

And here, let me say: When a beautiful woman thanks you, voice all low with modest surprise and whispering tonal modulation, it gets a man past a lot of impossibility. For a minute, it seems as though she might really value the sentiment, which ups the ante on whatever is said next. What I do is I start talking — explaining and over-explaining what I thought of the rough cut of the film I just saw, as if my opinion mattered. About there, Brooklyn Decker starts the cutting of the avocado. She listens.

“The problem is, your character is likable and the people in the movie treat her in the most unethical way. They just kind of use her.”

Brooklyn looks right at me then. She can establish — and hold — a gaze without much effort. “So you hurt for her then?”

Not exactly. She was being conned. But I find myself nodding. My obligations to her beauty have become overwhelming. “Yeah.”

“That means I did a good job, right?”

“Good job” is something you tell a kid at soccer practice. And rhetorical questions, asked by a woman whose hair is the kind of blond that feels like the mother of everything blond, are generally not worth answering. But yes, good job, for what that’s worth.

Sounds like not much! Also, beautiful women make men lie. Men really have no choice in the matter, you see. Are you guys taking notes? Also, what does the mother of everything blond look like? Barbara Eden, do you think?

Okay. I can maybe ignore the fact that it’s poorly written, but I can’t forgive the patronizing tone. The ultimate takeaway, here, is that Brooklyn Decker isn’t actually a human. She is simply an empty vessel for a male reader to fill with his own collection of concepts about idealized womanhood: childlike, caring, demure, sexy, approachable, warm, attentive, quiet, domestically inclined, eager to please.

In other words, not a real woman at all.

***

Time out. I could have ended this post here, and I almost did. But something bothered me each time I scanned through these words. Some voice inside me kept asking: “So?”

So what? It’s a fantasy version of a woman written for men who are in the mood to fantasize. Is there anything wrong with that, really?

Well… here’s the thing. Let’s flip this script. Let’s say I’m a heterosexual woman writing about a heterosexual man. A male swimsuit model. He’s merely a swimsuit model, known for his frame. Let’s say he even makes me dinner. He cuts the avocados just like Brooklyn did. So I write the same piece, only plugging in the variables with classically masculine concepts of manhood — strength, confidence, virility, problem-solving, aggression, and so on. Does my final article read anything like the above?

No. Not even close. Why? Because a fantasy man is idealized for knowing how to serve himself, and a fantasy woman is idealized for knowing how to serve a man. In order to write that same piece, I’d have to truly believe I was superior to my interview subject.

There’s not a word in that damn article that suggests Tom has one ounce of genuine respect for or interest in Brooklyn, outside of What Brooklyn Can Do For Tom.

As a woman, I can’t help but have a problem with that.

So, Mr. Chiarella, if I could somehow establish — and hold — a gaze with you through the internet, I would. And once I had gazed at you just long enough to have you feeling a little unsettled, I’d tell you this:

Good job, for what that’s worth.

Oh god, I think my eyes are bleeding from those snippets. That person has a legitimate writing career and we do not? WHAT.

Brooklyn Decker Confession: for a while her workout videos were on my ExcerciseTV OnDemand channel and I did them religiously for a few months. They were actually pretty good.

Yeah. I have NO IDEA. And I had no idea she had workout videos, but I wouldn’t doubt they’d be good. They appear to be working for her.

No….words……

It’s fitting that you started this post saying you hate movies. Because the post actually went on to explain what I specifically hate about a lot of movies, to the point that I have rants and break the occasional nose. I HATE that many (ok most) movies portray women as one of two caricatures apparently based on male perception and ideals. The first: the easy-going, funny and smart but never to the point of being threatening, and always effortlessly gorgeous woman. The second: the harpy, demanding bitch. The first sounds a lot like putting a woman on a pedestal but it’s not. They both reduce us to convenient caricatures, apparently for easy processing by the male brain.

This is why complex, real female characters always, always stand out to me. The point is not to paint women in the best light possible in films and literature. The point is that these caricatures are left behind.

EXACTLY. Elizabeth Bennet, Emma Woodhouse, Bridget Jones, Jane Eyre, Scarlett O’Hara…. all women with imperfections. Snotty; clueless; “fat”/lonely/smoking/insecure; plain; mean, respectively. Real women who last long after they have been put on the page. Because they’re not intended to be just put on pedestals.

It’s articles like these that make me happy to be in my profession, happy to have been trained how to be tough. I eat men like that for breakfast, and revel in the fact that when I establish and hold their gaze, they know I’m looking deep at them and finding them … lacking.

Awesome post! “And the breasts, ah, yes, always the breasts.” is one of the worst sentences I’ve ever read.

Right? Also, thank you!

F*ck yes.

Hells yeah.

yikes, that guy is a schmuck. I would love to read about you interviewing a swimsuit model, by the way. especially if he is cutting an avocado

I think that if I ever interview anyone, I am going to absolutely require that person to cut an avocado for me.

I wonder if Decker reads these articles about her afterwards, and I wonder what she thinks about them? Me, I better note to never accept an interview request from a writer for Esquire, because my reaction would be entirely, I FUCKING MADE DINNER FOR YOU AND THE ENTIRE TIME, YOU WERE THINKING WITH YOUR PENIS???

Good guests don’t objectify their hosts.

I’ve wondered the same thing about anyone who’s interviewed. I feel like if I was in that position, I’d never dare Google my name for fear of what I’d find… such as articles like this, for example.

Seriously brilliant. Why do men like this always need to a reduce a women to what she can do for him and what she looks like. He is basically trying to justify his own objectification within his own article. He basically says that she wants to be objectified. That’s coming dangerously close to “she wanted to be raped.” I’m not saying that this horrible writer was ever implying rape, but I think they both fit into the same culture that says that women are there to serve men and do whatever they want.

Some would make a case that a woman who agrees to have semi-nude photographs of herself taken for a magazine is basically agreeing to be objectified. She has no reason to complain about it, because hey: she CAN’T. She’s complicit, right? And this train of thought leads directly into the victim-blaming aspect of rape culture –if she didn’t want to be raped, she wouldn’t have worn that outfit, she wouldn’t have been in that place at that time, etc., etc.

Which is obviously a load of horseshit. All of it. It doesn’t matter in the end if she’s wearing something modest or something skimpy, if she’s out at a bar late at night or tucked away in the relative safety of her home, if she is letting sexy photographs of herself be taken or not, if she’s classified on the whore/slut or virgin/prude end of the spectrum. Women are always “asking for it” because they are women. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Attitudes such as these and articles such as the above can be traced back to a fundamental lack of respect.

It’s difficult to truly objectify someone if you see them foremost as a person. Even if you are tremendously attracted to that person.

Anyone can appreciate the beauty, the sexuality, of a woman — or a man — without reducing her/him to a demeaning or dismissive caricature.

And yeah, wow. Didn’t realize I had so much to say in return.

Wait, are you sure it wasn’t the chicken that he thought she made? I’m loathe to make anyone chicken dinner after that stupid Marriage Proposal Chicken.

If I’m going to propose to anyone, it’d be over a perfect Steak.

She CAN’T MIND?! “Don’t worry boys, not your fault for looking. She’s too hot. Boys will be boys.” I WANT TO BURN THIS MOTHERFUCKER.

Your last line made me crack up.

wow. is it me or does it sound like tom had a bit of a chubby while just “hanging out casually, playin’ it cool” with Brooklyn in her apt?

i don’t mind you sharing that article or the cover three times because until RIGHT NOW, i didn’t know who she was…and even now that i know her name…i still haven’t quite gathered why i should care, which, if tom were a good feature writer, he would’ve gotten past his massive erection to telling us about who the hell she is.

UGH, yes. And I mean, fine, whatever, but dude! Stop slavering over her and write a coherent article. All I got out of this was that she was blond and has boobs. I suppose that’s what they think all Esquire readers want? Blecchhh.

How exactly does this guy (presumably) make a living as a writer? Gross. Insulting. Blecchchhch.

reading those excerpts makes me want to throw up.

and if i were andy roddick, i’d hunt this em-effer down and beat him with my tennis racket for mind fucking the shit out of my wife in my own home .

the part about the breasts? jesus.

oh yeah. and this:

http://consumat.files.wordpress.com/2008/07/109824.jpg

to quote one of the great feminist minds of our generations, “ew, AS IF.”

BUH! GROSS!

Lyn, where ARE you? I’m getting whiny.

Kathryn! I’m sorry. I disappeared, eh? But your comment made my day, so at least there’s that!